On Intersex Representation

Disclaimer:

by Amy Stone (@amylstone1)

The Greek mythology of Hermaphroditos narrates a winged love-god who fused with a nymph and thus possessed both male and female traits. The sculpture, Sleeping Hermaphroditos, in the Louvre was based on this Greek myth. Myths about combining male and female traits in one body are also part of Plato’s theory of love, popularized in the song “The Origins of Love” in the musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

Throughout history, there have always been individuals born with ambiguous sex characteristics, whether that ambiguity is about hormones, chromosomes, or the appearance of genitalia. For much of human history, these differences were considered unproblematic and involved no medical intervention.

The term “hermaphrodite” has a complicated, controversial history. Modern use of the term hearkens back to the Victorian era, when the terms “true hermaphrodite” and “pseudo hermaphrodite” were developed as a kind of medical terminology. In her history of the Victorian medical field, Alice Dreger describes the complexity of “hermaphrodite” as a diagnosis.

Close analysis of the literature on hermaphroditism also reveals that there was not a single, unified medical opinion about which traits were essentially or significantly male or female. The sexes were constructed in many different (sometimes conflicting) ways in hermaphrodite theory and in medical practice, as medical men struggled to come up with a system of sex difference that would hold. Ultimately, it was not only the hermaphrodite’s body that lay ensconced in ambiguity, but medical and scientific concepts of the male and female as well. Still, however mixed and multifaceted sex was shown able to be, however overt and extreme the disagreements about the nature of sex, medical men never ceased to assume that in the final analysis there were still two and only two distinct, “true” human sexes. And, as the end of the century neared, it became certain that any given body could and would only be entitled to one.

Victorian doctors puzzled as to how to best categorize individuals with ambiguous sex characteristics into “two and only two distinct ‘true’ human sexes.” And early medical literature obsessively focused on how to transform ambiguous sex characteristics into ones that were visibly, clearly male or female.

These efforts to medically transform bodies intensified after World War II, as doctors became involved in increasing numbers of surgeries and unnecessary medical treatments of intersex infants. The medical tradition developed in the Victorian era turned into a system of medical treatment that often resulted in scarring procedures, dramatic sex reassignments, medical voyeurism of intersex bodies, and intersex children being lied to about their condition by doctors and parents. One of the dehumanizing aspects of this medical treatment is that pictures would be taken of the naked bodies of intersex children and adults with their eyes covered in black boxes to obscure their identity, pictures that were then published in medical textbooks.

In the 1990s, the Intersex Society of North America began as a coordinated effort to create networks about intersex people and stop childhood intersex medical interventions. The society was formed by intersex adults, many of whom had their own medical histories hidden from them by doctors and parents. The term “hermaphrodite” has been reclaimed by some intersex activists, reclaiming a stigmatizing term in the same way that some people reclaim words like “queer.” For example, for many years the newsletter of the Intersex Society of North America was called Hermaphrodites with Attitude. On their website the Intersex Society of North America describes the term “hermaphrodite” as stigmatizing and misleading as a description for what is better referred to as intersex conditions or identities. More recently, some medical advocates have pushed for using the term “disorders of sex development” to describe intersex medical conditions, a move that is resisted by some intersex activist groups as being too medicalizing.

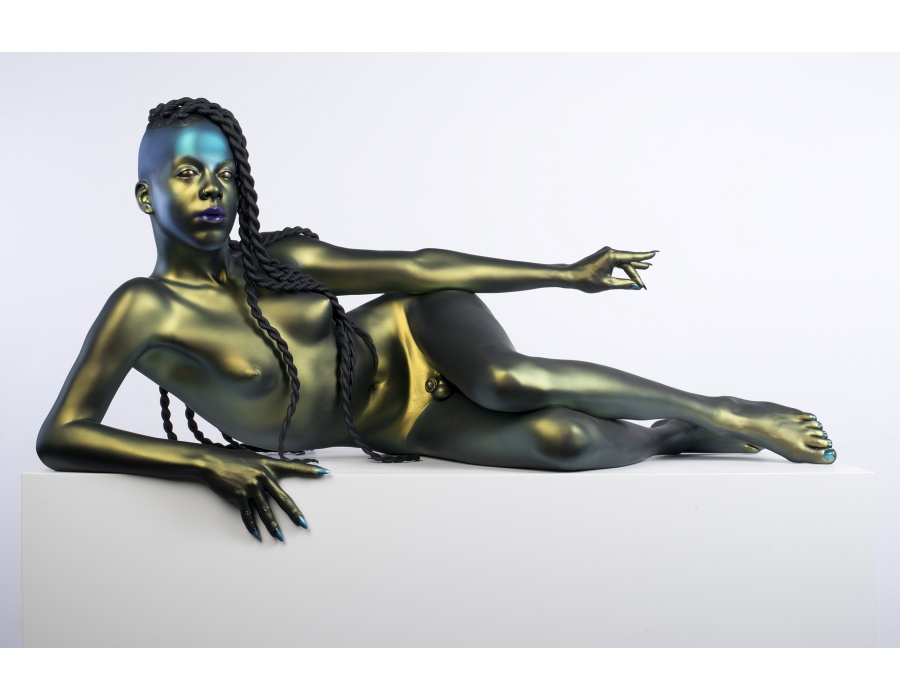

Intersex activism has grown to include work by activist filmmakers like Pidgeon Pagonis, scholar activists like sociologist Georgiann Davis, and organizations like interACT. One notable intersex artist is Juliana Huxtable, a Black visual artist who uses multiple mediums to express messages about gender, sexuality, race, and the body.

This 3D printed sculpture by Frank Benson of Juliana Huxtable, an intersex and transgender visual artist, captures this work by intersex activists to bring humanity to representations of intersex people. Modeled after the Sleeping Hermaphroditos statue of Greece, the sculpture Juliana shows the beauty and personality of an intersex woman in a way that is a stark contrast to the medical pictures of intersex people. Huxtable’s curves and expressiveness are on display in this sculpture, providing a window into her creative genius.