Trans Temporal: Finding Community across Generations

Disclaimer:

by Melissa Gohlke

Avenues for finding transgender community abound in 2019: the internet, support groups, organizations. Transgender activism is widespread giving voice to those silenced for too long. I am fortunate to live in a time when my daughter can transition with the support of long-time transgender activists like Cynthia Phillips, access to counseling, and mentors within the millennial trans community.

In an era of open discourse about trans lives and issues, an assessment of the history of finding community has value as we interpret current notions of trans identities within the contemporary milieu. Untold chapters in the Alamo city’s history offer insight into pathways that introduced variant gender expression into San Antonio culture in the early 20th century and beyond.

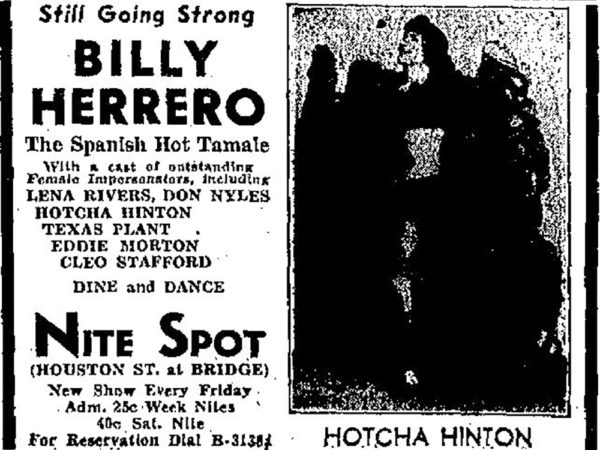

As early as 1906, female impersonators graced Vaudeville stages across the city. Venues such as Electric Park and the Vaudeville Theater hosted troupes whose male stars donned female garb much to the delight of audiences. While Vaudeville shows popularized such entertainment, the decades that followed, particularly the 1930s and 40s, ushered in a time when gender crossing acts became a staple of nightclubs and cabarets sprinkled throughout San Antonio’s theater district. The Pansy Craze—a fascination with drag performance and sexual difference—swept across the country in the wake of the Harlem Renaissance and San Antonio clubs profited from this allure. The Nite Spot, Gay Paree, and Riverside Gardens featured female impersonators.[1] Performers like Hotcha Hinton were professional female mimics (many were heterosexual) who traveled the country as part of companies such as the Jewel Box Revue and Boys Will be Girls. Many of the entertainers came from the west coast and hailed from famous drag venues. The Garden of Allah in Seattle served as home base for Hinton and other fellow performers.[2]

![Gay Paree program (2) Gay Paree souvenir program (interior), General Photographs Collection, MS 362, UTSA Libraries Special Collections [3]](https://transamerican.mcnayart.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Gay-Paree-program-2-600x450.jpg)

Acceptance of trans bodies as a commodity for public consumption only extended to the confines of clubs and cabarets. Once performers stepped outside of establishments they were expected to leave their female garb and makeup behind. Not all performers complied with these social strictures. In 1935, seven men performing at the Royale Dinner Club were arrested on morals violations and indecent exposure when a customer at the hotel next door filed a complaint. Georgie Kaye and his College Boys spent several hours in jail while awaiting sentencing. Their arrest prompted police raids of the club in attempts to end the deviant performances.[4] Despite the popularity of female impersonation as an art form, taboos against gender transgressing persisted for those who enjoyed crossdressing and transvestism as a way of life and chose to do so in the public realm.[5]

Jim and Cynthia Phillips married in 1958. Unlike most newlyweds, the couple both wore nightgowns on their wedding night. Jim (aka Linda) enjoyed crossdressing and Cynthia knew of this inclination prior to their nuptials. Little information existed for those in the “gender community” who might be curious about others who enjoyed crossing genders. Cynthia recounted that, “Linda was always interested in her ‘underground’ gender community. Back in the 50s and 60s there was very little information to the public, but she never felt she was ‘the only one.’ Some of the magazines in adult book stores would have ads in the back and if they looked ‘authentic,’ she would answer them. You had to be very careful back in the 60s, as you could be arrested in what the ‘authorities’ considered pornography. Even if it didn’t have anything to do with sex.”[6]

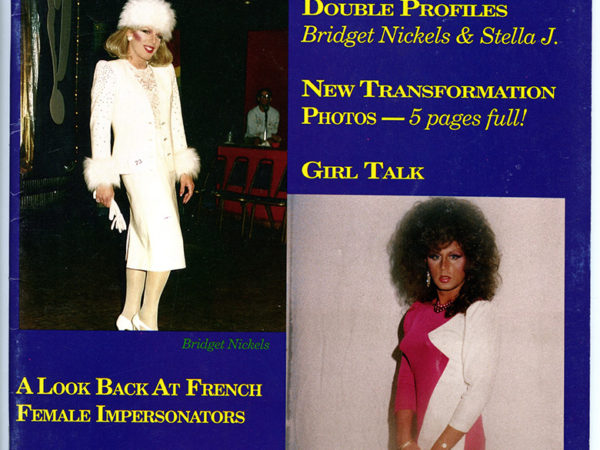

As time progressed, information became available through the work of trans pioneer Virginia Prince. Prince had paid her dues in the 50s for corresponding with a transvestite. She was arrested and jailed on several occasions and knew the cost of engaging in what was perceived as a transgressive lifestyle.[7] Despite this, Prince understood the need to connect with those living gender conflicted lives. In 1960, Prince published Transvestia magazine and several books that had profound impact on the trans community:The Transvestite and His Wife (1967) and How to be a Woman Though Male (1971). Prince’s publications and the formation of the crossdressing organization Tri Ess (Society for the Second Self) were strictly for heterosexual male crossdressers.[8]

For the Phillips’ and many others, trans publications functioned as a conduit for finding community. Linda reached out to several individuals over the years in a search to communicate with other “TVs.” Through tentative connections, Linda formed friendships that lasted for many years and served as the foundation for discovering community. Other ways of finding other crossdressers proved more serendipitous. One morning while lounging in bed, the couple heard mention of the meeting of “men in dresses” at a San Antonio hotel. Cynthia tenaciously pursued the lead and discovered the newly formed group, the Boulton and Park Society. This discovery proved to be a transformative moment in their lives. The Society put on the Texas “T” Party, a tradition (the largest gathering of crossdressers in the world at the time) that the Phillips’ organized and hosted for over 10 years.

The importance of communal connections and educating the broader public prompted Linda and Cynthia to boldly take their message to a national audience. In the early 1990s, the couple appeared on several television talk shows including the Joan Rivers Show, the Maury Povich Show, and Geraldo. While this might have been a risky move, audiences on these programs proved receptive to the experience of learning about trans lives. The Phillips’ also took their message to local colleges, “explaining the Transgender lifestyle and what made Gender People ‘tick!” Cynthia recalls that many psychiatrists and psychologists sat in on [their] talks and asked questions. Student response papers to the presentations, revealed how students’ perceptions about crossdressing altered drastically after hearing the couple speak.[9]

Over decades, trans visibility in San Antonio was manifest in a myriad of ways. Vaudeville performers, female impersonators, and pioneering activists all contributed to evolving trans identities. While early years may not have been fertile ground for formal interactions, subsequent decades provided avenues for coming together and forging community. Present day activists fighting anti-trans legislation owe a debt of gratitude to early advocates for trans rights. They helped lay the groundwork for talking openly about gender variance and in doing so, made life a little easier for San Antonians transitioning in the new millennium.

[1] San Antonio newspapers ran ads for Vaudeville shows featuring female impersonators and later for shows at clubs and cabarets the city’s theater district.

[2] Don Paulson with Roger Simpson, An Evening at the Garden of Allah: A Gay Cabaret in Seattle, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

[3] While most female impersonators used the term Mr. in their names, Hotcha Hinton lived her life as a woman and insisted on being addressed as such.

[4] “Female Impersonators held in Morals Case,” San Antonio Express, July 5, 1935.

[5] Transvestite or TV was a common and preferred term within the crossdressing community up until the late 1990s.

[6] Email interview with Cynthia Phillips, April 9, 2019.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Virginia Prince,” [https://www.uvic.ca/transgenderarchives/collections/virginia-prince/index.php], accessed May 18, 2019.

[9] Phillip’s interview.