How Masculinity and Femininity are Treated Differently

Disclaimer:

by Amy Stone (@amylstone1)

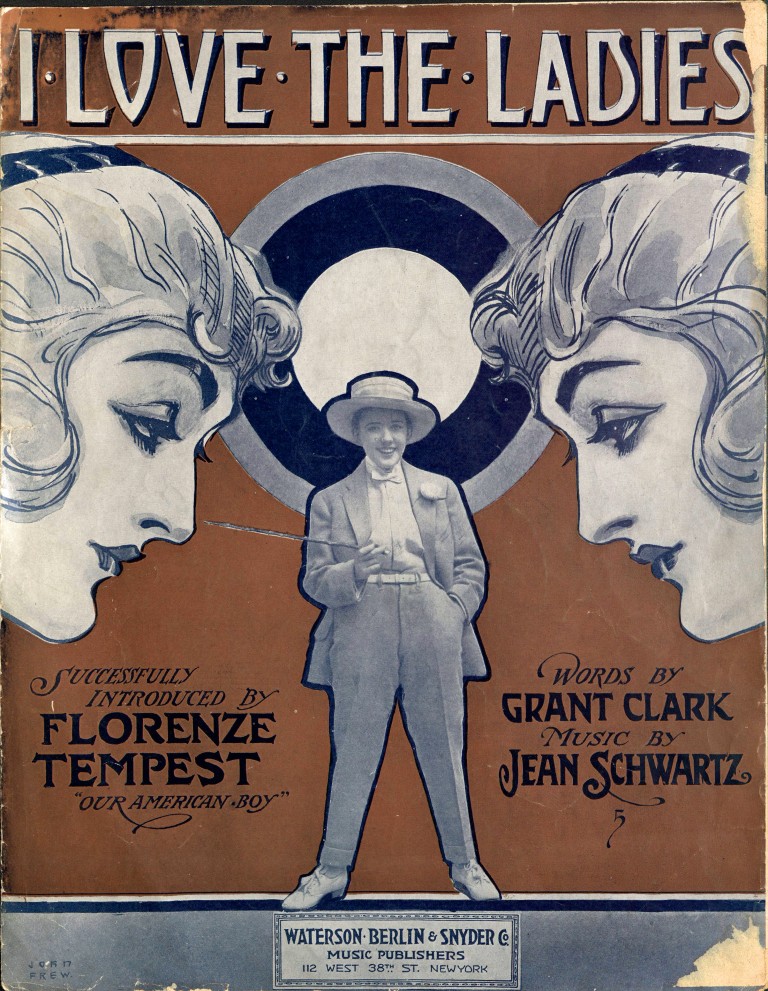

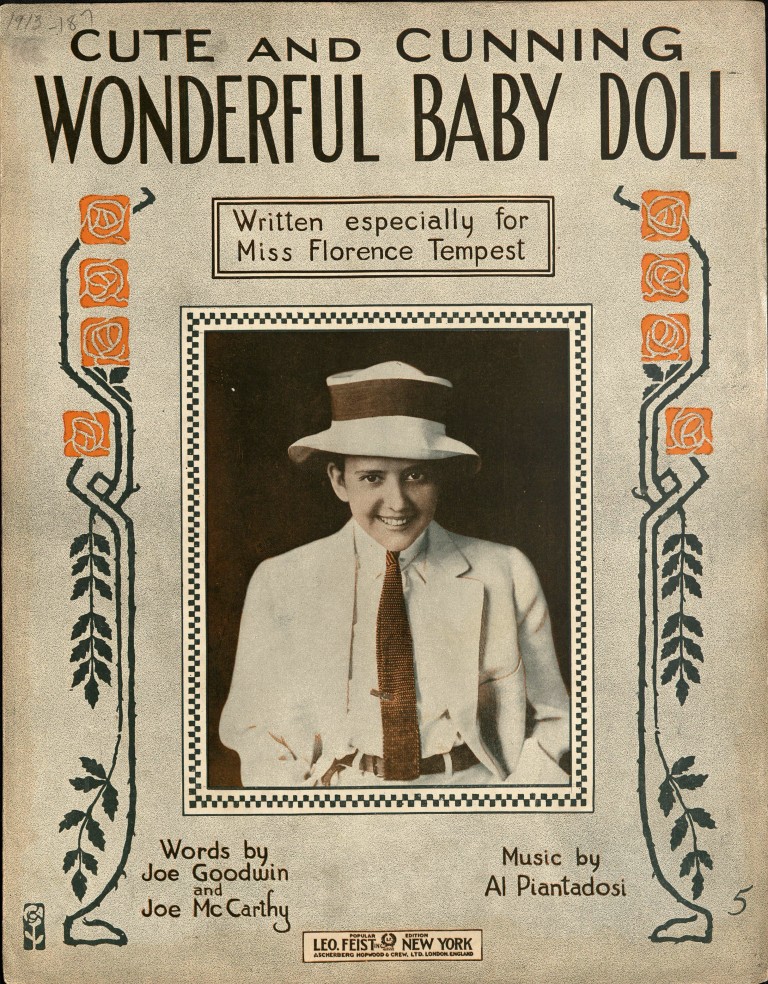

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, both male and female impersonators were popular on the vaudeville stage in the United States. Male impersonators were individuals who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) but often performed in suits as dandies on the stage, singing tunes traditionally sung by men. Female impersonators were individuals who were assigned male at birth (AMAB) and dazzled audiences with their persuasiveness as women. One of the most famous female impersonators was Julian Eltinge, who was a cultural reference until the 1960s.

Although male impersonators frequently performed on the vaudeville stage, this art form did not persist in the same way as female impersonators, who became household names. Male impersonators were considered less dazzling and entertaining than their female impersonator counterparts.

This blog asks the question of why there is a different interest and perception of AFAB masculinity compared to AMAB femininity? Culturally, we treat tomboys differently than sissies, drag kings differently than drag queens, and female masculinity differently than male effeminacy. We see this in the art world as well. There are more depictions of male effeminacy, trans women, and other feminine transgressiveness and a relative lack of images of female masculinity, trans men, and butchness. When I went to the exhibition Transamerica/n at the McNay, I was in awe of the number of depictions of female masculinity, trans masculinity, and butch identities. Yet these images are still outnumbered by depictions of femininity.

Part of this difference is that masculinity and femininity themselves, regardless of who performs them, are treated differently in society. Masculinity is often considered more inherently serious and valued above femininity. Femininity is often trivialized, considered entertaining yet less valued. These understandings of masculinity and femininity shape how people understand gender transgressiveness.

When people who are assigned female at birth perform masculinity, the reaction to this performance is sometimes dramatic. Scholar Jack Halberstam in his book Female Masculinity describes female masculinity as generally received by others as pathological as “a longing to be and to have a power that is always just out of reach.” Female masculinity is often understood as attaining power, value, and privilege. For example, being a tomboy can be a source of pride and identity in a way that being a sissy historically has not. Overall, this performance is not typically seen as entertaining or an aesthetic that can be consumed by a mainstream audience. For example, representations of butch lesbians and trans men have only recently become a part of mainstream television and movies.

There is a much longer history in the arts and media of representations of people who are assigned male at birth performing femininity. In the theater, female impersonation was a required part of Elizabethan Shakespeare and Japanese kabuki, in which males play all the roles. As shown in the documentary The Celluloid Closet, effeminate characters have long been used in movies as entertainment, often tokenized humorous sidekicks or gags. Due to the popularity of shows like Ru Paul’s Drag Race and Pose, most Americans are familiar with drag queens but may have never seen or heard of drag kings before.

People who are assigned male at birth performing femininity is simultaneously marked as different, used as entertainment, and policed with violence. Effeminacy for example, is a word specifically to describe when people who identify as men or boys engage in traditionally feminine activities or ways of behaving. Although society has changed dramatically, there is still a lower tolerance socially for effeminacy than for female masculinity. In her book about masculinity and high school boys, sociologist C.J. Pascoe discusses how even minor kinds of effeminacy, like caring about one’s clothes and enjoying dance, can lead to bullying and teasing. This policing of effeminacy is part of the larger devaluation of femininity, and the reaction to effeminacy is shaped by the values projected onto male bodies relinquishing the power of masculinity and embracing femininity instead.

Overall, masculinity and femininity are treated differently in society, so the expression of female masculinity and effeminacy in art also have different meanings.